“To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge-and, therefore, like power”.

(Susan Sontag, 1977)

When film theorist Laura Mulvey talked about “Male gaze” for the first time in her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” back in the seventies she was most probably unaware of the repercussions that the term would have in the generations to come. Mulvey, advocate of the theories of Freud and Lacan, discussed in her acclaimed essay a voyeuristic way to look at women in narrative cinema where visual pleasure or scopophilia, appears to be the province of men. In the realms of the Male Gaze, women are simply passive objects, bearers of the look and the many meanings attributed to them but never active, never makers of that meaning.

What made Mulvey’s arguments relevant for our present reality is the fact that she talked about something we are sadly still experiencing: inequality. We live in a socio-political reality that perpetuates differences through a traditional gender binary discourse that opposes “male versus female”. These gaps occur in many fields of our daily lives, one of them, and a very influential one, is the ambit of visual representation. The facts and figures according to a report from 2017 by The British Journal of Photography speak by themselves revealing that 80% of photography students are female but only 15 % of professional photographers are women. How can that be possible?

During an interview with the online magazine of the British Journal of Photography, Photographer Joanne Coates, an analogue photographer and co-founder of the platform Lens Think, came out with this strong affirmation: “I could never afford an expensive camera. When I finished my foundation degree, my granddad handed me down his medium format camera -it showed someone believed in me and my work. That idea propelled me to using that camera. I’m also quite a shy and awkward person, and when taking portraits I find it easier to be able to slow down, to take time to speak to people and to interact with them as I’m working – which the film camera enables me to do.”

Coates makes visible in her statement a few essential factors that in my opinion have turned film photography into a democratizing medium accessible to all sort of people no matter their position in society in terms of gender, class, race and sexual orientation :

-The implicit low-cost of acquiring an analogue or lomography camera,

-The gift to be able to slow down and connect with those in front of the objective,

-The freedom to create regardless of the previous training and professional equipment

It might seem contradictory that analogue photography is these days experiencing a cultural and aesthetic revival in a digital dominated world, but it is actually in this context of an overabundance of images that the subversive presence of film makes more sense than ever. This subversion has been the playground of the myriad of female* photographers who are daring to challenge the dominant discourse created around women as objects to be depicted and not as active agents responsible for the representation of their own identity.

Today, multiple voices are using analogue photography to represent another depiction of women (and by extension men*) far from the one imposed by the “Grand Narrative”. They are challenging their own “otherness” by representing a more fluid vision of gender roles and equality through a demystifying lens.

Most of you might be wondering, how is film photography counteracting the “male gaze”? My theory is that due to its characteristics, traditional photography acts as a potential medium to deconstruct the dominant narratives around the photographic field where a photographer is mostly depicted as a male with a gigantic objective (needless to say, the phallus analogy is imminent in every mind), where photography is oppressed by the evil standards of technical perfection and where the pressure to produce beauty obscures the possibility of an alternative canon.

It is precisely in this context of deconstruction that a new way of looking (and photographing) is making an entrance. Perhaps one of the reasons for the reappearance of film photography is its recent widespread popularity in the mainstream with photographers like Petra Collins being commissioned to photograph Gucci campaigns or Harley Weir’s film photographs appearing in the pages of Vogue. Apart from that, it seems that contemporary film photography aims to liberate photography through the freedom to make mistakes, the acceptance of the imperfection and the use of low-tech gear.

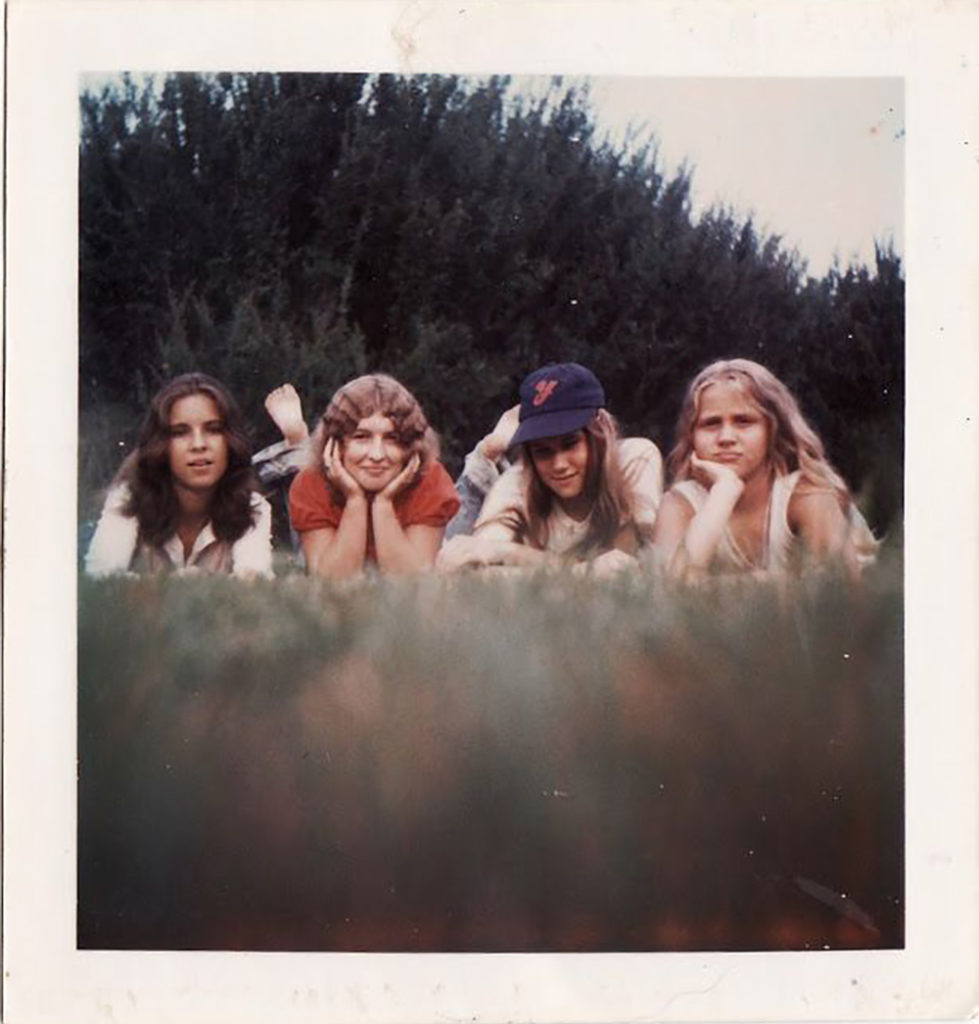

Those beginning their ways in the analogue world know that sometimes the process is not entirely under control, one must accept a light leak in a camera found in a forgotten drawer in the attic, dust when developing the film is also quite common, the undeniable trace of time and oblivion, and even an underexposed roll count among some of the experiences that traditional photography confronts newbies with. These “mistakes”, the absence of subject or even technique, instead of disqualifying a photograph, show a more human and real face of the medium, and by extension, of human beings, especially women, who had to deal traditionally with the burden of being flawless, passive objects to be looked at. The subjects photographed in the case of film photography, pose unafraid in front of an imperfect objective. A real depiction, a tender and sensual image appears giving space to a new camara vision infused with emotions and authenticity.

The comeback of traditional photography has enabled amateur photographers to not only demystify the imperfection, the noise, the chemical errors of the medium but also to give credit to genres such as the family album and the snapshot, very much attributed historically to the amateur female photographer due to their emotional connotations. These days, the popularity of the aesthetic of the family album has served as inspiration for this new generation of photographers overtaking traditional photography in an attempt to exert ownership over their own “otherness”.

Rare Polaroid Picture from 1975

Chantal Convertini 2019 @paeulini

As a brief recap, what makes this new generation of young photographers turn to a less sophisticated, less automated and less acute camera technology?

- Authenticity. The experience feels more real and sensual than the automation and glossiness that digital images offer.

- Inclusiveness. From Stieglitz to Weston, the parameters to evaluate a “good photograph” were based on technical perfection, these days this idea has been replaced by a more inclusive one where the tangible photographic expression has taken relevance.

- The human factor. Film photography entails the candour of the grainy imperfection, the impossibility to control the results and the imminent ephemerality of the process. Its tactility engenders an organic feeling that is linked to the flaw and therefore with a more human quality.

- Nostalgia. The longing for the aesthetic of a romanticised past craved by a generation of millennials saturated with digital perfect images. Shows like Stranger Things have created room for the triumphal entrance of the medium in the mainstream, and the need to reconnect with the authenticity and the sublimation of memory that entails.

- Being present. Analogue photography makes us slow down the pace, look and reconsider our visual options, if there is enough consumerist waste in the world, an ecology of not only things but also images makes sense nowadays.

I think we are in a very interesting time for photography where there is room for exploration for any gender. However, the revival of film photography brought a new way of looking, a new idea of beauty fostered by intersectional approaches, women (and human beings in general) started finding themselves more accepting of how they actually look. The female gaze is kaleidoscopic, it reinterprets another vision of the women granting it with integrity and at the same time, it paves the path for a new critical dynamic beyond the one imposed by the hetero-patriarchal system.

As our capitalist society is based on a culture of images, social change is made possible only through a change in visual culture: it’s clear that what we are currently experiencing is a reevaluation of life – old ideas are being crushed, making room for a new Gaze. From the “Male Gaze” of Laura Mulvey to the more inclusive Lacanian concept of “The Gaze”, the dominant discourses based on racialization, age, gender or class among others, are facing a transformation towards a “resistance gaze” where the role of the spectator is equally crucial in the formation of meaning.

exhibited at “New Masculinity” by @curatedbygirls 2017

Traditional photography, rescued from oblivion, has contributed immensely to the enterprise of granting not only female* image-makers with the agency they always deserved but also has made evident that a change in visual culture towards a more fluid gaze was necessary for a change in our society.

*Both cisgender and transgender women/men