South African-American painter, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, was born and raised in New York, with her exiled South African father and her mother. She also grew up in Harare and spent her adolescence in Johannesburg, where she now lives. She was drawn to Art at an early age as a process of working out what home & belonging mean. She obtained her BA from Harvard University (2004) and her MFA from the School of Visual Arts in New York (2008).

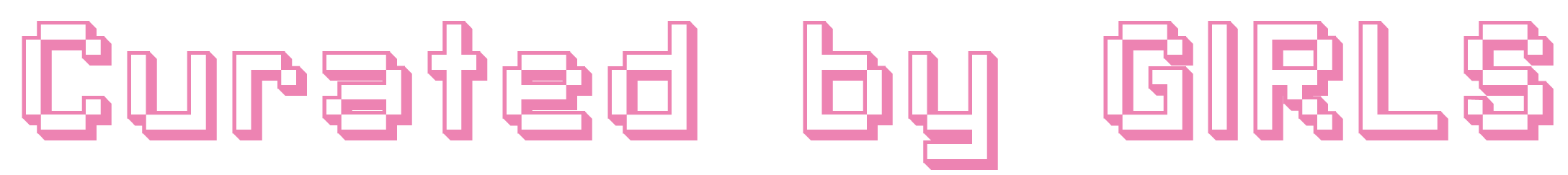

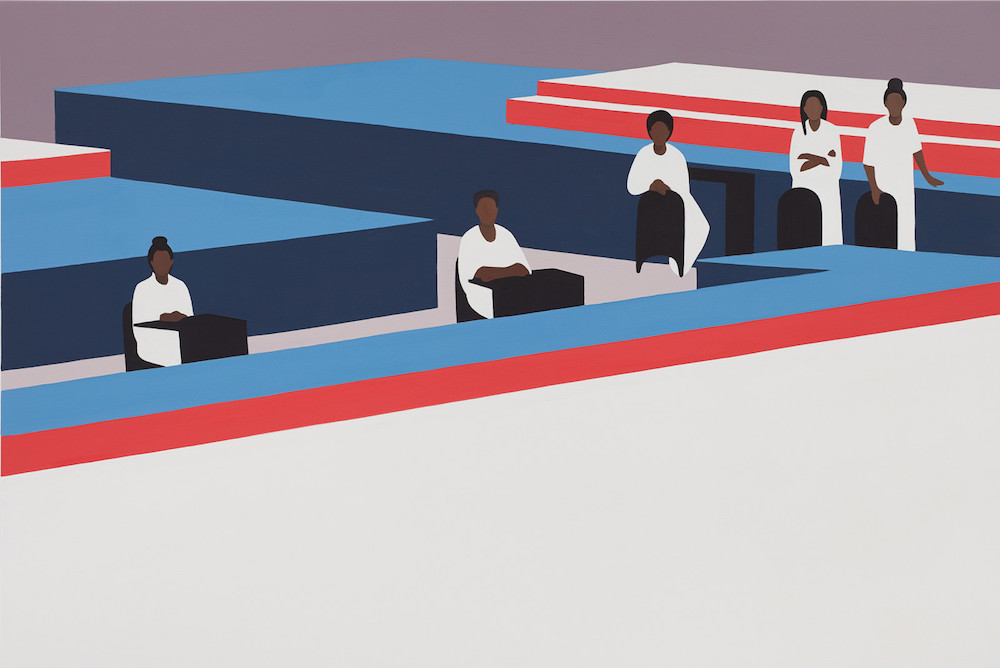

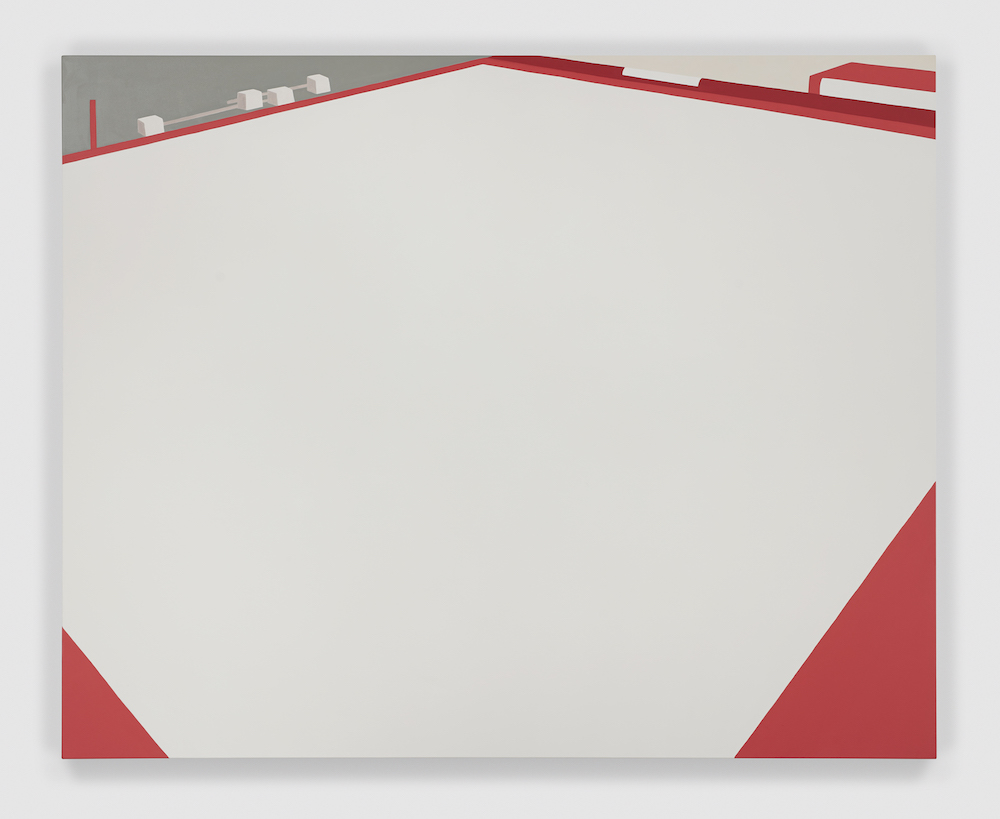

With Gymnasium, her first solo exhibition at Stevenson in Johannesburg, Thenjiwe brings forward issues surrounding the black body and defies the white supremacist structure of an elite sport that has been dictating body ideals and promoting the idea of the perfect person. Through a sophisticated mix of vibrant pastel colors, the artist reimagined the people in a gymnasium as people of color, with faceless figures to emphasize the idea of a Black woman standing in as the ‘every person’. The gymnast becomes important no matter who she is.

Nkosi’s figures are decidedly not painted in peak moments of athleticism, but rather, the artist is capturing moments preceding and following the execution of a move, or the aftermath of failure. Shifting focus away from the fact of success or defeat, Gymnasium spotlights the humanity engaged and set aside in the shift from human to performer, youth to labourer, person to demigod, and the reverse.

Thenjiwe opened up to Curated by GIRLS about the origins of this series, how it started in a feeling of creative frustration, and the relationship between her work and her own identity. Read our interview below.

Routine

Moving Mats

The artist, like the gymnast, is witnessed and judged: trying, succeeding, failing.

Where are you from, where do you live now?

I was born in New York and grew up there and in Harare and Johannesburg. For the past decade though I’ve been based in Johannesburg. This consistency is a little strange for me because I like moving around. I’ve participated in a bunch of artists’ residencies over the years, which has given me the opportunity to be in a variety of places but for shorter periods of time than actually moving to a new place. For now, and maybe until movement is allowed again, it’s Johannesburg. I rent a studio about ten minutes by car from our apartment, where I live with my partner and our child.

How and when did you realise you wanted to be an artist ?

It’s hard to isolate one moment but I do think that certain experiences I had as a child played their part in my life taking this direction. Most important, I think, was the idea I had, growing up in the US, that my real home was elsewhere. My exiled South African father and my mother both spoke about South Africa as “home” – but we couldn’t go there. And so for me, there was this question: Well if that’s home, where are we living now? And even when we did eventually “return” to South Africa, it was a home that I was unfamiliar with. And so began this process of working out what home means, and what belonging means. And at an early age, I found that making things about these questions was a useful way of working through them. I guess I was in my late teens or early twenties when that was happening.

Fault

Start Value

Difficulty Value

Faceless figures have such broad symbolic potential. I’m interested in the idea of a Black person, particularly a Black woman, standing in as the ‘every person’. That this feels in some way radical should give pause for thought.

Your paintings have a very particular aesthetic. Can you tell us about your technique & creative process? What inspires you?

As soon I started taking painting seriously, in my second year in university, I became interested in the idea of removing visual information. Flattening and simplifying shapes and figures. At the time it was an intuitive thing, but now, in retrospect, I think it was always about taking away specific context so I could create a more universal figuration. I have used that technique very deliberately in the ongoing “Heroes” series of portraits, which I started in 2012. In that series, which is about expanding the idea of who gets memorialized, the flat colour backgrounds and simple blocks of clothing take time and place out of the equation. Thus collapsing or crunching time and geography.

In the “Gymnasium” paintings I found I could remove even more information, including facial features. The faceless figures bring a range of new ideas to the table for me, since they have such broad symbolic potential. I’m interested in the idea of a Black woman standing in as the ‘every person’.

The flatness is achieved by layering. I’m painting these paintings at least three or four times. The layering actually started because I wanted to get straight lines without using tape. Freehand painting is important to me – it gives the work a certain vibration. It makes it feel alive. I think that effect is produced by having to keep going back, using my eye, getting the angle as right as possible – but also knowing that it’s impossible to get it right. There is a tension that is created in that process. Sometimes I find it maddening but more often I find it a meditative process.

As an artist I often felt like that person from the Gymnasium series: performing in front of judges who come in different forms. And my performance was not just the paintings I make, but who I am, since my identity as a Black woman painter is so often foregrounded.

What prompted you to start the series “Gymnasium” and how did it develop?

The story of the Gymnasium paintings started in a feeling of creative frustration, which comes about periodically and which I’m learning to embrace. I’d been working almost exclusively on the “Heroes” series for a few years, and I was feeling like I needed to be doing something other than painting portraits. I felt it wordlessly and I knew I needed to trust that feeling. I was talking with my partner about this and he reminded me of two paintings I’d made years earlier. They both depicted the inside of a gymnasium. One was of a gymnast in the middle of the floor and some judges sitting in their usual positions around the floor, looking at the gymnast. I was open to that idea and I went back to look at them. At the time I painted them, it was the interior of the gymnasium that I’d been interested in. The feel of the arena, the geometry of the different zones. But now, when I returned to that one painting in particular, something else stood out for me: the figure of the gymnast. What I realised was that as an artist I often felt like that person: performing in front of judges, judges who come in different forms. And my performance was not just the paintings I make, but who I am, since my identity as a Black woman painter is so often foregrounded. Making that connection in my head was where this series began.

In one way these paintings are about me imagining a radically different space, one where the judgment, the witnessing, is all being done by people that I can identify with on a basic level. (…) it’s an exercise in imagining a world I would have wanted to live in – one where my “double consciousness” would not always have to be employed.

Spring Floor IV

Spring Floor VI

Spring Floor V

“Gymnasium’ suggests lots of references, undertones, dealing with issues surrounding the black body, and questioning race and identity. What is the relationship between your own identity and your work?

Elite gymnastics, like so many similar spaces, was created as a place to celebrate a particular idea of excellence. Which was, although it was not said openly, ‘white excellence’. For a long time, around the world, such spaces were protected as white spaces by colour bars of different kinds. But when that became no longer feasible, in the last century, people in authority had to find different ways of protecting the space. When you read what is still written about Simone Biles (a common phrase used to criticise her gymnastics is that she is “powerful but not elegant”), you see that that history is still very much with us.

This phenomenon — of white spaces opening up but developing alternative strategies of exclusion — is visible in lots of different institutions. And it was part of my life as a young person – in high school in South Africa, in university in the USA. Being one of the few, and having to develop ways to live with that. So in one way these paintings are about me imagining a radically different space, one where the judgment, the witnessing, is all being done by people that I can identify with on a basic level. It’s not meant to be some kind of ideal space, but on a simple level it’s an exercise in imagining a world I would have wanted to live in — one where my “double consciousness” would not always have to be employed.

By removing the particular features of the gymnasts I am reminding myself, in a way, that even when she is performing alone, she is part of a network of reciprocal relationships.

Beauty ideals, perfection, individuality are usually at the core of gymnastics…As you explained above, in your paintings you refrain to give the gymnasts and judges any identifiable features. What were your intentions?

I think there are two main things going on for me. First – and I spoke about this earlier – is the fact that faceless figures have such broad symbolic potential. I’m interested in the idea of a Black person, particularly a Black woman, standing in as the ‘every person’. That this feels in some way radical should give pause for thought.

The other thing has to do with the relationship between the group and the individual. This is something that I have been interested in for years. It informs my “Heroes” portraits. What is the function of the hero? What agenda does the hero serve? And the same applies to the world of sport. So at some level I’m wondering about this and working through it. I see how the gymnastics establishment, and certainly the media, fixate on the individual star, but through my research and personal observation I’ve noticed how the gymnasts themselves understand the necessity of the team. So by removing the particular features of the gymnasts I am reminding myself, in a way, that even when she is performing alone, she is part of a network of reciprocal relationships.

What’s next for you?

I’m painting all the time. I am continuing with this series, expanding it conceptually and aesthetically. But I have been contemplating looking at other sports too. I have an underlying interest in movement and physicality – it’s something that is personally important to me, and something that also informed the choice of the “Gymnasium” series. It feels like this series was the beginning of exploring that underlying interest, and I imagine that it will be part of the next steps for me, regardless of exactly what form the work takes.

Thank you so much Thenjiwe!

All images © Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Photo: Nina Lieska